Subcontinent Travel Journal

Alladin had his carpet and lamp. Today with a laptop and 747 ... away we go. Join me for another two months of exploration in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Small World

SMALL WORLD:

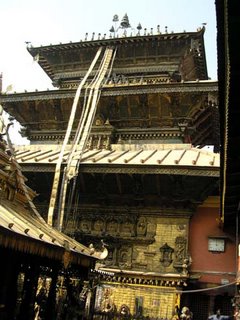

A Visit to Nepal

Shrill music suddenly blares from a nearby store’s street speakers adding to the cacophony of honking horns and human voices. Noontime traffic turns the streets to moving metal and glass, transforms the crammed sidewalks into a cotton merchant’s dream of nirvana. A curly-tailed dog stops to lift his leg against a planter from which bougainvillea riots to spread red blossoms across a grill and up a wall. A waiter comes with a fresh bottle of Everest beer. MooMoo’s – spicy, steamed Nepalese dumplings – sit well in our bellies, and we are content to lounge under our awning and watch the world of Kathmandu go by.

“Hey! Robyn! What’re you doing here?” The hail comes from a tall and very obviously American man with dark hair. A red-haired woman and two carrot-topped boys stop with him.

“Patti, Mark!” My daughter jumps up and leans over the planters that divide our table from the rest of the sidewalk to hug friends from the US Agency for International Development mission in Delhi and introduce them to me. Like us, they’re in Nepal for the Thanksgiving holiday. We shout to be heard over the honking of horns and high-pitched wailing of mountain flutes on the music store speakers.

As we talk, though, I recognize the song being played and remember the lyrics:

It's a world of laughter

A world of tears

It's a world of hopes

And a world of fears

There's so much that we share

That it's time we're aware

It's a small world after all.

“What a small world!” It’s the next afternoon. This voice is female and belongs to an attractive woman with an athlete’s slim, muscular figure and dark, curly hair. She has just come onto a balcony where we’re enjoying the spectacular views of high, intensely terraced hills stretching up and up to the sharp, jagged snow-covered peaks of the Himalayas, a frieze of ethereal splendor, far above any self-respecting horizon. Here, words fail, belief in the supernormal begins. Truly, this is a “land of clouds” and “the abode of gods.”

“Becky,” Robyn’s voice goes up in disbelief. “What a surprise!” We’re a thousand feet above the closest hill village, a one-street settlement called Nagrakot. We’re staying in the last guest house on the road, reached via a track we wouldn’t consider jeepable at home but which we negotiated in a mini rental. It’s impossible we should know anyone here … but there you are.

In the evening after a strenuous afternoon of trekking, the guests gather around a tabletop fireplace, smoke rising up a flaring hood and filtering around its edges to water our eyes. Next to me, tanned and blonde in the firelight, is a South African elections expert who has just come from Afghanistan. She and Robyn talk about common experiences there. Later, we discuss LET’S NOT GO TO THE DOGS TONIGHT, and I tell them about meeting the author, Alexandria Fuller, in Jackson, Wyoming, and how, as it turned out, she was a close friend of good friends of ours in Malawi. “What a small world,” people say.

We are six Americans at dinner. One, an Alaskan who owns a remote resort near Homer, knows Alan and Ann Simpson from Cody and has worked with Wyoming environmentalists – familiar names to me. We talk about Louise Erdrich’s HEART MOUNTAIN. “It is, indeed, a small world,” we say.

Anecdotes about just how small it is fill the next hour. “Just last night,” Robyn contributes, “We were at a Thanksgiving dinner in Kathmandu and one of the guests looked familiar. She’s Russian, which should have been a clue, but it wasn’t until she mentioned Patti, who we had just seen down in Thamel … Then it clicked … . You know her.” Robyn turned to Becky. “It was Zoya. I hadn’t seen her since … .” And, so it went until the fire burned itself out, and we made our way through hillside gardens of marigolds grown into shrubs, morning glories, mock oranges, and poinsettia trees to our rooms and beds warmed by hot water bottles where we would dream of morning and the fire of sunrise on the high, snow-capped horizon.

“Honest to God,” I say. “It really is a small world.” Robyn and I are crowded into a glass-walled room filled with rows of plastic bucket chairs separated by narrow aisles. Every chair is occupied, the floor strewn with empty cardboard lunch containers and empty water bottles. It’s standing room only for passengers hoping to embark on flights to places like Dubai, Bangkok, and Delhi. Occasionally, by some sort of osmosis or whisper campaign, word circulates that flight something or other is loading, and people rush to the door. Sometimes the loud speaker system blares a confirmation.

What has grabbed my attention, though, is the number of people in the lounge that I know. The family from Delhi is there … we had shared a ride to the airport together. Near the door I see a man from Portland. We had chatted away the time while waiting for clouds to clear over the Himalayas and our flight to Everest to leave. Two rows in front of us, another man, someone Robyn had known in Washington and who had been at dinner with us the night before, sat waiting for a plane to Bangkok. Near the front of the room, I can see a sleek blonde head bent under earphones and recognized her as another member of the American mission in Delhi.

Robyn looks around, says, “Yeah,” and goes back to our Sudoku puzzle. What else is new. But lyrics lilt through my mind …

There is just one moon

And one golden sun

And a smile means Friendship to ev'ryone

Though the mountains divide

And the oceans are wide

It's a small world after all.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Life's Tough

“They may have had thousands of women in their harems, but life wasn’t that easy for them.”

So says our guide, leaning earnestly toward us, speaking of the Moghul emperors, particularly of the three most famous emperors of the 16th century, the ones who built the great monuments in Agra and created the short-lived city of Fatehpur Sikri.

“Maybe,” he says, “fifteen percent of their time was spent with the ladies. For eight-five percent they were doing war.”

We understand. We’re in a war of nerves, steel, and flesh, driving to Fatehpur Sikri on a narrow road designed for carts, but being used by buses, lorries, cars, motorbikes, motor rickshaws (I’ve learned to call them tuk tuks), camel taxis, bicycles, and pedestrians. All are going as fast as their respective feet, hooves, or wheels will carry them. All are hogging whatever right of way they can carve from the mob, channeled by the macadam which drops precipitously in a tire-eating, pastern-popping, ankle-breaking way. No one goes there. But petty merchants and entertainers, hoping for a customer, jump not infrequently onto the road. Even a boy with a dancing bear interrupts our passage.

War, the kind deliberately designed to produce fatalities, was a full-time occupation for the Moghuls, our driver says, conducted almost entirely by elephant, camel, and horse cavalries. Foot soldiers fleshed out the battle front and, sometimes, by their sheer numbers, frightened the opposition into surrender. But no one counted on them to do much killing. No one counted on much killing at all. War was rather like the roads of India are now … a place of bluff and bluster, where the loser retreats, the winner goes forward. With luck, no one gets killed.

We pull out to go around a bus, our driver’s horn blaring. There’s a car headed straight for us. I grab for a handhold as our driver’s head jerks back and he takes his foot off the gas. My mouth drops open in disbelief. We’re idling along, now, the oncoming car becoming huge, the bus alongside us a moving wall. “Go,” I shout, my voice one of many. “Step on it.”

Way too late the driver seems to realize where he is. He snaps out of his reverie and does step on it, again leaning on the horn. The bus is blaring, the arms of a man with a donkey wave, the face of the oncoming driver can be seen, imperturbable. His expression says that this happens all the time.

Maybe it does. He brakes, and we squeak through.

The Moghuls had nothing on us. Akbar, it is said, bluffed an enemy who could field tens of thousands of men with nothing more than gall and nine hundred mounted troops. The rebellious prince had led his uprising, believing Akbar too far away to do anything about it. Indeed, it was impossible.

But unwilling to be outmaneuvered in such a blatant manner, Akbar force-marched the most mobile part of his army, and appeared in the disloyal principality in record time. The prince, seeing himself surrounded, thought his intelligence wrong and surrendered.

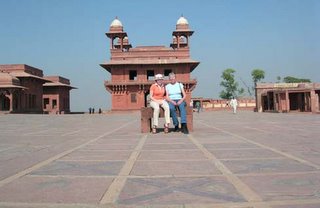

Back to the Moghuls’ sex lives. We’ve just gone through the outer walls of Fatehpur Sikri and are idling along past the remains of long, stone buildings that are divided into small cells. “The market,” our guide says. The road begins climbing and, ahead of us along a high ridge, we can see a collection of peaked domes standing on pillars – typical Central Asian construction.

What’s any of this got to do with sex, you ask? These particular domes, indeed the entire town of Fatehpur Sikri as it developed under the Moghuls, came into being because a holy man predicted that Akbar’s wives would finally give him sons. And so it came to pass … but only after Akbar’s first wife spent her confinement living near the holy man’s retreat at Fatehpur Sikri.

Akbar was convinced. The place was a baby factory. So, rather than moving his wives back and forth from Agra, he relocated his capitol, built himself a city.

The child-bearing years came and went. New problems arose and drove him to relocate once more. Thus, fifteen years after it was built, Fatehpur Sikri was left to the heat, the holy men, goats, sheep, snakes, and, eventually, to tourists.

We sit on a bench in the middle of a life-sized Parcheesi board, where the ladies of the harem once danced and sang as human Parcheesi pieces, and we listen to more stories about Akbar. As promised, most of them concern war, and these weren’t always bloodless.

Nor was our trip to Fatehpur Sikri without casualties. We’re getting a new driver.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Singing the Colors

“Red, six, two blue, two, gold, red, three.” The weavers sing the Hindi words, the melody line flowing through half-tones of four notes, fingers dancing to the chant, pulling red, blue and gold threads between string stretched tight around massive rollers. The hiss of wool on wool builds the sound; the soft whisper of round blades slicing through threads is faint as a memory. “Red, three, two gold, blue, two gold.”

Slam! Down come the forks, packing knotted threads into the intricacy of a growing pattern. Slam! Slam! Slam! These are the kettle drums of the weavers’ music.

Back go the fingers, four sets or more to a loom, filling in background color on the next row, waiting for the song to lead the colors to their appointed places, to create the intricate designs and the velvet nap of an Agra carpet. One chant cascades into another, each carpet with its own lyrics and music, repeated and repeated, one voice dying away, another taking its place, piling century upon century, time becoming a solid unit without change.

These timeless, almost wear-proof tapestries sing to their owners as the weavers sang in their creation, the colors shimmering in sunlight, iridescent beneath candles, the nap shining when turned one way, darkening the other. And, they have traveled far, these singing carpets, covering floors in Arizona and California, shimmering once in Versailles’ famous Hall of Mirrors, gracing London salons for the past five centuries, and filling the palaces of the Moghul Emperors.

I imagine them spread around us as we sit on a wall in an elaborately carved pavilion that served as a prison for Shah Jahan and look up the Yamuna River to the marble tracery of the Taj Mahal.

The old shah would have relaxed, not on the wall but on Agra carpets created by the fingers and songs of his subjects while he stared at the ethereal sight of the Taj Mahal, the tomb he had built for his much-loved wife, a woman of laughter and music. Together, they would have spent hours on such carpets, their memories woven into curving leaves and climbing vines.

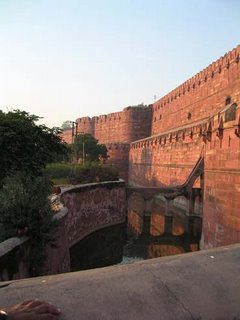

History moves on. The carpets and the singing of the colors stayed the same. Three centuries later, the British flooded into these same palaces, seeking the protection of the exterior walls of Agra’s massive Red Fort. Six thousand English came through heat reaching 136 degrees Fahrenheit, in carts overflowing with carpets and ayahs, followed by horses and bearers.

They tacked their carpets, colors alive even in the killing heat, over empty door frames and along pillared arcades, spread them over stone floors, creating stifling rooms where their owners lay in fetid disorder for months, disorganized and demoralized, fearing the uprising of the Indian troops that killed whole British garrisons elsewhere, afraid of the rioting in the town.

Bad things happen, but the singing of the colors goes on, as inexorable as the flow of life, itself. I think of this as we watch the weavers’ fingers flickering through the wool, listen to the music building yet another carpet. Even on the loom it is developing a jeweled quality, beginning its own song. “Two red, gold, six, gold, two red, blue.”

Slam! And another row is complete.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

The Tailor

“You are needing only loose covers,” he says, a doll-sized sewing machine dangling from one arm. “This, I am finishing by eight o’clock.”

I look at our two big chairs and the bolt of fabric and shake my head. It is already four in the afternoon. No way can he cut, fit, and sew zippered covers for the cushions and these massive and thickly upholstered beasts in four hours. Maybe this tailor, who has been sent around by one of India’s big department stores, is speaking in metaphors? Maybe he means eight o’clock on some night next week. Whatever. We’ll obviously have him around for a while.

Not that he takes up much space, being a very short and slight person with shoulders and hips the breadth and thickness of those of an anorexic, twelve-year-old American girl, with arms as thin as those of a Belsen-Belsen survivor. His face, though, is firmly fleshed and defined with determination, his eyes black and hard, his hair thick and black.

“This is good,” I say, ever the diplomat. “But to work tomorrow, too, is okay.” And, I hear my own voice and realize that I’m beginning to speak in simplified English.

I go back to my Think Pad. The tailor gets an iron and ironing board from the maid. I edit photographs. Behind me the board squeaks and the iron hisses. An air purifier squats in the corner, slurping up the fetid Delhi air, spitting out a slightly cleaner product. My Photoshop program eats four pictures in some unaccountable way. An hour passes before I think to look around to see the thin figure bent over one of the chairs, a length of cloth draped haphazardly across its back and arm. Snip. His scissors, sharp as stilettos, cut a six-inch, curve more or less following the shape of a chair arm.

My mother’s sewing genes wince. I close my eyes. It’s going to be a massacre. Tattered bits of cloth will soon be hanging off the chairs. We’re going to need another 14 meters of fabric. We’re going to … .

I won’t look. I’ll find another place to work.

That’s the best idea. Think Pad in hand, I set up shop in the living room. Cocktail and dinner time arrive. From the study comes the hum of the sewing machine. Something is happening in there. I won’t look.

I do, of course, but only a peek as I walk past the door. He’s haunches down on the carpet, barely visible beneath heaps of cloth. One knee seems to be propping up his chin, the other juts out at right angles to the body, his hands feed fabric through the speeding needle of his sewing machine.

Dinner is over. We are considering the medicinal qualities of brandy when … .

“Finished, Madam.”

The tailor is standing in the door, his sewing machine again hanging from one arm. “I am going now,” he says. It is eight-thirty.

We crowd the study door, see a scene of devastation, a room strewn with thin strips and snips of fabric. They cover the floor, form heaps on every surface. Lint has turned the red carpet to a near white, but … against one wall sit the two chairs, resplendent in their new clothes. The cushions bulge against their covers, fabric shapes in smooth curves over arms and backs, nips where it should and makes nice, tight edges above the floor. The chairs are beautiful.

“I DO believe in miracles,” I say. “I really do.”

Total Cost, fabric and labor: $20

Total Time: 4 ½ hours

Mehrangarh Fort, Jodphur

The solid “twack” of mallet against ball, the rumbling thunder of hooves galloping toward a goal, the cry of “my shot, my shot.” Sound drifts out of the past, shouts and female cheering underlain by the slightly deeper encouragement of eunuchs. It’s polo I’m hearing, the game originated by a Maharajah of Jodhpur to amuse himself and his ladies, played for the royal court. Here, in Jodphur, is where it began.

Court paintings show richly dressed women swinging their long mallets, horses at a gallop. In the style of the period, no emotion shows on chiseled faces, but arms saw on bits, skirts fly, action indicating anything but retiring modesty, point to an aggressive desire to win.

We are in the treasury, have passed through the massive gates of Mehrangarh, a monolithic giant rising like some great Gulliver from the Lilliputian city clustered at its feet, nevermind the other two million people flaring out in a vast wrinkled tapestry of urban sprawl across the plains. Before the two million were born, elephants made dust storms where they now live, beat their way toward, then up the endless ramps of the Mehrangarh, climbing, climbing, carrying royal parties to the palace, the intricately carved cap atop the wall-topped cliffs.

“Two-thirds of the inhabitants were women,” our guide says. “Can you guess why?”

An Indian family passes, smug in belonging, in personal ownership of the past – these gold-leafed pictures, this treasure belongs to them, to previous incarnations of their friends, relatives, perhaps even to their very selves. It is theirs, a warm, almost remembrance, a certainty to hug close as a cloak against the heavy smog of a cold night.

“Guess why?” Well, duh. With maharajahs who went in for a hundred or more wives plus another two or three hundred concubines, each having their own female servants, the wonder is that only two-thirds were women. Twenty thousand or more soldiers were garrisoned there, as well, but they seldom, if ever, had the opportunity of breathing the rarified air at the top of the mountain, of enjoying the cooling breezes that whispered through the fretted, intricately carved sandstone screens that composed the outer walls, of looking over the parapets at a world as remote and inaccessible as Tibet.

Life within the walls, for all the splendor of construction, the glitter of colored Belgian glass, the marvel of mirrored walls, would have been grim and crowded.

There was no privacy, of course. It probably wasn’t missed. Water would have been in short supply, the smell of unwashed bodies oppressive in the desert heat … even with the light breezes. Smoke from the cooking fires in the courtyards would have seeped everywhere. Excrement from animals and humans would have added to the mix and risen above the ladies’ perfumes.

Danger. The maharajah’s amusement room, where his ladies danced to entertain him, was spotted with strategically placed mirrors, set to allow him to see right hands – the hand that might hold an attacking knife. Obviously, no ruler trusted either his guards or his women.

You would think, though, that most women would think twice and three times about attacking their lord, suti being a prized custom in Rajasthan. Prints of little hands lined up in rows on a wall by one of the gates, imprinted as the doomed soul passed this point for the last time, memorialize the women who joined their husbands on their funeral pyres. Fresh silver paint applied to these old hand prints and chains of flowers indicate that modern reverence for this custom still exists although the last known suti was in 1949.

We lean over an extruding balcony, peering into space, a view the suti designees would have seen just before their last walks. Maybe, less walk and more sway, a gait supported by copious quantities of opium.

“They ate it for breakfast,” our guide comments with a matter of fact shrug. “It was how they lived. They were all addicted.”

No wonder this strong point, seemingly impregnable to pre-20th century weapons, fell on three separate occasions.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Time Warp: Pushkar Camel Fair

You can step back in time. You can rub shoulders with the ages, with a thousand or more cultures, races, and religious beliefs, be transported to a place between temporal planes. So far as I know, no book makes reference of this time warp, although it opens once a year on the scrub-covered, cone-shaped Arvali hills of Rajasthan during Kartik Purnima, a high, holy Hindu celebration. Not even the “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” with its catalog of the rare and the brilliant, touches on this point on Earth where a broken macadam road makes a sharp curve, where the verges are lined with a few trees and many vendor’s stalls. If you pay attention here, you will spot an opening through tent walls, one just wide enough to admit a camel taxi. Pass through and into the timeless.

People come by train, horse, camel, and truck from Delhi, Ajmer, Jaipur, or desert oasis. Nomads from the pre-Christian centuries arrive by watering stages driving their herds. Passport-carrying, twenty-first century denizens, smelling of suntan oil, dressed by Sierra Trading, descend from lines of tour busses. Holy men garbed in spiritualism if not cleanliness, beards reaching for the ground, arrive on feet callused and grilled by desert sands. Villagers and warriors, royalty and casteless merchants approach on mules or camels, in the backs of trucks or hanging from the sides of motor rickshaws. Styles span the centuries – here a gown Jesus of Nazarus might have worn, there a dress Scheherazade would have envied, over there a toga, on that head a Mongol helmet. I wore jeans.

Tent cities rise among the scrub-pocked hills, neighborhoods developing, the babble of a hundred languages and a thousand dialects creating a mat of sound, underpinning the wail of flutes, the punctuating demanding wail of a curved horn, the bawl of camels, the barking of dogs. Horses whinny and scream, people shout their wares, and beggars really do whine. “Momma. A rupee, Momma.”

Three hundred thousand people come. Many sleep with only a blanket to protect them from the freezing desert night, are surrounded by their animals strung out in orderly lines. These, like the threads of a spider’s web, cover the scrub hills in intricate patterns, running past tents, paralleling high walls created from yards of patterned cotton, bordering freshly created tracks that will be soon dug into deep trenches by the volume of traffic.

The hobbling system comes from remote history. One rope goes down; is pegged. Short ropes attach to it, two spaced one foot apart for each animal’s hind legs. A second long rope parallels the first, neck ropes snaking up from it. In between, animals stand, side by side, prevented by their restraints from moving out of place or harming each other. Recalcitrant beasts earn the extra joy of a doubled-up front leg. Truly difficult cases are on the ground, learning their lessons the hard way.

Manure is not a problem. At the lift of a tail, a boy appears to scoop up the offering and carry it to squatting dung workers who pound the balls together into pancake-sized patties that are laid out in the sun to dry. When evening comes, the dust of the day is augmented by smoke from fifty thousand fires or more, pungent, smoky fires made from the patties.

It is evening, and visitors flock to the hilltops by camel cart and horseback, talking and smoking and watching the sun set. Watching the sun go down is a literal possibility. Smoke, dust, and other air pollution render the sun a weak globe of light, a star of dubious power, harmless to the eye.

Torches, firelight, lanterns spot the night, warm glitters across the land. But on one high hill a great glow reflects against the sky. Electricity reaches there, turning the grounds of a stadium to day, giving racing horses and camels a visible track to run on, roars of the crowds seeping through the night. Beside the stadium, Ferris Wheels circle – reds, blues, and greens swooping around and around in a brilliant light display.

A main camp street spins out from the town, lined day and night by vendors. Colorful cotton walls, provide privacy. Behind this wall the screen of a television flickers. For five rupees, men, women, and children of all centuries can see the Moghul invasion of India or watch Alexander the Great conquer the known world. Next door, a folding chair invites passersby in for a hair cut. Beyond, an old man sits cross-legged on a table rolling out unleavened bread, the cook fire at his elbow, pots of simmering food minded by his veiled wives lined up buffet style along the street.

Everything you could want is for sale – animals, jewelry, swords and knives, lutes and flutes, piles of clothing, and good luck.

It’s the Brahmin festival of Kartik Purnima in the holy city of Pushtar, the Tirth Raj or king of pilgrim centers and home to the only temple dedicated to Lord Brahma in India – Brahma, the creator of all. Here, legend says, Brahma dropped a lotus petal. Where it landed, water sprang up, creating a sacred lake.

“You will learn everything,” our guide, Lotus, explains. He is a lovely man dressed in flowing white with shoulder length hair so black it shows blue highlights and with skin the color and consistency of mocha chocolate. We are on a Hindu spiritual walk, following the way of holiness, the way taken by daily processions of the faithful and their most sacred symbols. We follow it to a ghat – steps descending to one of the 52 bathing areas on the lake, each possessed of special powers. On all sides buildings drop into the water, the whiteness of the walls punctuated by the other ghats.

We already have good luck yarn wrapped around our wrists and spots of red between our eyes, symbols provided by our twenty-first century guides to protect us from shills out of the past who will try to separate us from our rupees with the offer of spurious blessings. Our charms don’t work. We sit on the steps above the holy water and are conned out of amounts up to twenty dollars each by Hindu acolytes. Caught in the moment, I consider us cheap when my daughter holds out and only offers twelve. Then, the acolytes come around to take back the flower petals and coconuts we’d been given, and I remember the warnings. Oh, well. Experience costs.

Noise follows. There are the timpani of bells, each clang signifying a prayer. There is the singing as the processions go by, each dedicated to its own manifestation of Brahma, to one of his thousand names and attributes, filling the narrow streets. There is shouting and praying and calling of person to person. Overall, the loudspeakers blare music and announcements and more prayers, and notice that the camel judging is over or the horse racing about to begin.

Some things don’t exist. Privacy, for one. Meat dishes for another. Bland food for a third. Cleanliness for a fourth. Some things aren’t missed. Schedules and deadlines head the list. Many things are enjoyed – color, sound, smells. The Pushkar Camel Fair. It’s like a deep well, waters rising, bringing up shards of old pottery, bits of hair and bone and thought, mingling with air and smoke and sound, fizzing and boiling, creating a froth of life, a separate moment in time where everything under the sun meets and mingles. Pushkar. The camel fair.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Monday, November 07, 2005

HORN PLEASE

God, Vishnu, Buddha, Allah or Henry Ford put the horn on the steering column for a purpose. Raucous music, maybe. Big, white HORN PLEASE signs, prominently displayed on the backs of trucks, cars, and autorickshaws in Delhi’s streets, invite everyone to join up, to play in the street band … blow, blast, squawk, beep, toot and hoot. Anyone can play. No talent or musical direction needed, just enthusiastic participation.

Street life adds to the orchestration. Eggwallas, foodsellers, kiosk owners, beggars call their wares or needs in a dozen dialects, the iron wheels of carts rumbling a deep bass accompaniment. Radios blast from cars and shops, guards hail each other, ladies in brilliantly colored saris haggle over the price of an orange – no one has heard of noise pollution, couldn’t hear for the noise.

Over all, like some prehistoric beast comes the long, mournful and deep cry of a train. And, late in the night, after the day’s orchestra has exhausted itself, the great, winding sounds of passing trains still rise above the city, reminding of the long, spiraling horns that once sounded from city walls, heralding the approach of kings.

Sunday, November 06, 2005

New Delhi, First Impressions

Beyond the doors of the Indira Ghandi customs shed, 'eau de third world' meets the nose, a smell composed of old cook fires, exhaust, the faint bouquet of uncollected ordure, and, sometimes, like tonight, a hint of gunpowder. In other times and places, the addition of that acrid odor means revolution. But in New Delhi on 4 November 2005, just past the 15th day of Kartika, it signifies only post-Diwali fireworks.

Cars don’t travel in orderly lines here. Creative driving rules. In the white, midnight light around the terminal, vehicles lead with their noses, behave like molecules of water coursing through rapids, hurtling sideways around obstacles (a bus or bicycle rickshaw), braking just a hair before crashing headlong into a rival passenger door, easing cannily over a center line to charge into a five-foot gap. Parking space belongs to the imaginative, the innovative. Confusion is universal.

And the people; the cacophony of voices. Is this what God had had in mind when he created the Tower of Babel? Eighteen languages with an alleged one thousand dialects are spoken by the 16.7% of the earth’s population that inhabit India. They seem to be all represented here tonight.

Space. It’s the illusion of the western mind bred from vast frontiers and empty acres, of dry, crystalline air and limitless sight. Take those away, and the elbow (already bruised from the airline's idea of space) becomes the weapon of choice.

Along the Way

Fellowship of the air. Never seen these new friends before; never will again. Lynn from Omaha with her short brown hair cut for business, but with style. Rod, a tall and well-proportioned man, a transplanted Michiganer who met his fiancé on a flight to Dubai. “One that was just like this one,” he says.

I can imagine. He overflows his seat in enforced intimacy, plants his feet on the crowding bulkhead wall to stretch his legs, talks of dirt bikes and fishing.

Where to put the coffee cup? How to juggle a book, blow up an inflatable pillow, toe off a shoe with elbow pinned to skin, metal chair arms rubbing holes in elbows. Minimal comfort requires a group effort.

Tiny fingers play spider, creep overhead, tangle in hair. “Corinda,” her mother says.

Nevermind. We play finger hide and seek across the seat back, the child and I, her dark eyes from Mumbai … old Bombay … wide with mischief

The night is brief, gone in the spasm of cramped legs and feigned sleep. Every watch eats time, jumps forward, hands whirling ahead. Twelve, One, Two, Three and the DC-10’s nose unearths the sun, winkles it off the seabed, sends it up over waterlogged land.

Amsterdam ahead.

Shippol. Seabed waters shed and channeled. Men with light blue eyes, startling in their clarity and fixity. They have wrested a land from the sea.

And, the women, tall and fair, speaking accented English,

“My flight’s not on the board,” I say to one. I’m not complaining but asking a question:

“What do I do now?”

She checks my boarding pass. F-7. “Here you are,” she says, trust in the system firm in her voice. People flow around us, mostly attached to wheeled boxes built to hold computers and overnight needs.

F-7 is miles away. What if I walk it only to find nothing there? “It is clear,” she reads my expression. “F-7.”

Who in America, where change is the only certainty, would trust a boarding pass issued a day earlier?

She does.

She was right.